Andrew Marble

marble.onl

andrew@willows.ai

Dec 27, 2023

I’ve implemented inference code for three difference language model architectures from scratch recently. The models are:

Llama21: a transformer architecture with many different available models;

Mamba-ssm2: a new alternative to transformers that was recently published;

Distilbert3: an transformer embedding model used for information indexing and retrieval.

You can run these on a decent computer with no external dependencies (except the weights, examples of which are provided). I wanted to describe the choices I made, mainly the language, and some of the implementation details.

Why Fortran

Fortran is a high level language, particularly with respect to linear algebra. It supports matrices and vectors including arithmetic operations, slicing, permuting and reshaping the way that Python does with Numpy. Compared to C, Fortran lets us type matrix and linear algebra formulae more naturally without worrying about pointers, keeping track of dimensions, etc. As an example, in C we need to keep track of offsets into arrays and dimensions as in the code below, whereas in Fortran we index into arrays. Additionally, matmul is an intrinsic function in Fortran while it isn’t in C.

// C

int loff = l * p->seq_len * kv_dim; // kv cache layer offset for convenience

s->k = s->key_cache + loff + pos * kv_dim;

matmul(s->k, s->xb, w->wk + l*dim*kv_dim, dim, kv_dim);

! Fortran

s%key_cache(:,pos,l) = matmul(xb,w%wk(:,:,l))

Example of multiplying a vector and weights, C vs Fortran

Fortran also has built in memory management, meaning in particular we don’t have to worry about freeing memory we are no longer using like in C.

I’m talking about C as the alternative because the other thing we want is to make our code as fast as possible for given hardware which in practice means a compiled language that allows hardware specific optimizations. Fortran is naturally fast, with available compilers such as Intel Fortran and GFortran/GCC that are mature and include lots of optimizations. For example we can compile with options like loop unrolling and ignoring certain types of error checking. We can also use vectorization on CPUs that support it. With Fortran’s built in matrix intrinsics, we can also compile with external libraries like BLAS that include optimized linear algebra routines. Additionally it is possible to link in C code to take advantage of CPU vector intrisincs or other low-level routines. Fortran also allows easy parallelization using OpenMP. The overall effect is that Fortran provides the best of high and low level programming, making it easy to write mathematical code at a high level and easy to drop down to assembly level routines where more control is needed.

I’ll mention what I see as some of the weaknesses: Fortran doesn’t have an official standard library, though it has a de-facto one that’s currently a work in progress4. So far I have worked almost entirely from scratch, for example I’ve written my own case conversion functions, regex type parsers5 etc. that if nothing else are more error prone than well tested versions. It also, in my opinion, doesn’t have great support for strings. For example all strings in an array have to be the same length. Apparently it does have Unicode support but I have not investigated this sufficiently and in one case still have an embarrassing hack6 to filter out Unicode characters. Also, all integers are signed, making (at least for me) C-style bitwise operations confusing and better done in C.

Luckily, none of that stuff is really core to AI code which is really just a lot of repeated matrix operations. My goal has been to write a fast core script with no dependencies that can be used to do AI inference and incorporated into a larger project as needed as well as adapted to particular hardware. I focused on Intel and AVX2 intrinsics and plan to continue to focus there (although I would love the opportunity to adapt it to one of the AI specific chips being developed).

That pretty much summarizes why I’m working with Fortran. I don’t think you could come up with a shorter, faster, more portable and more easy to read code for running an AI model than what you can with Fortran. There’s lots of competition now but I believe we’re going to see growth in simple, purpose specific codes and that’s where Fortran will play. I’ve implemented three different LLM architectures in Fortran. In the rest of this post I’ll briefly describe the code architecture and some key points about loading the models in to memory and fast inference.

Architecture

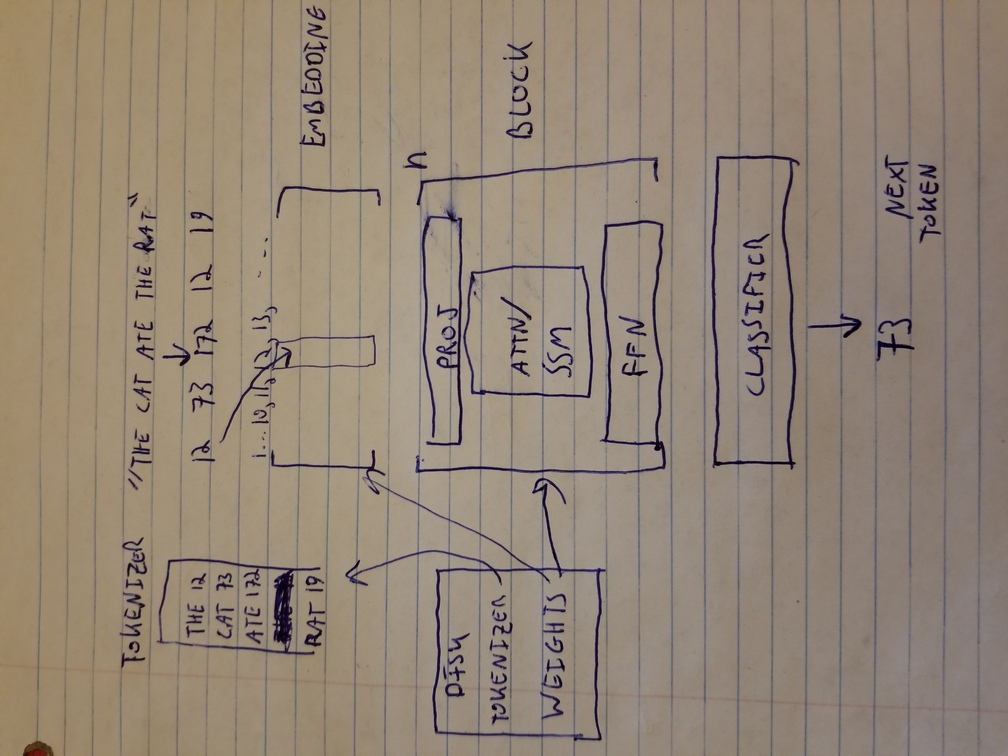

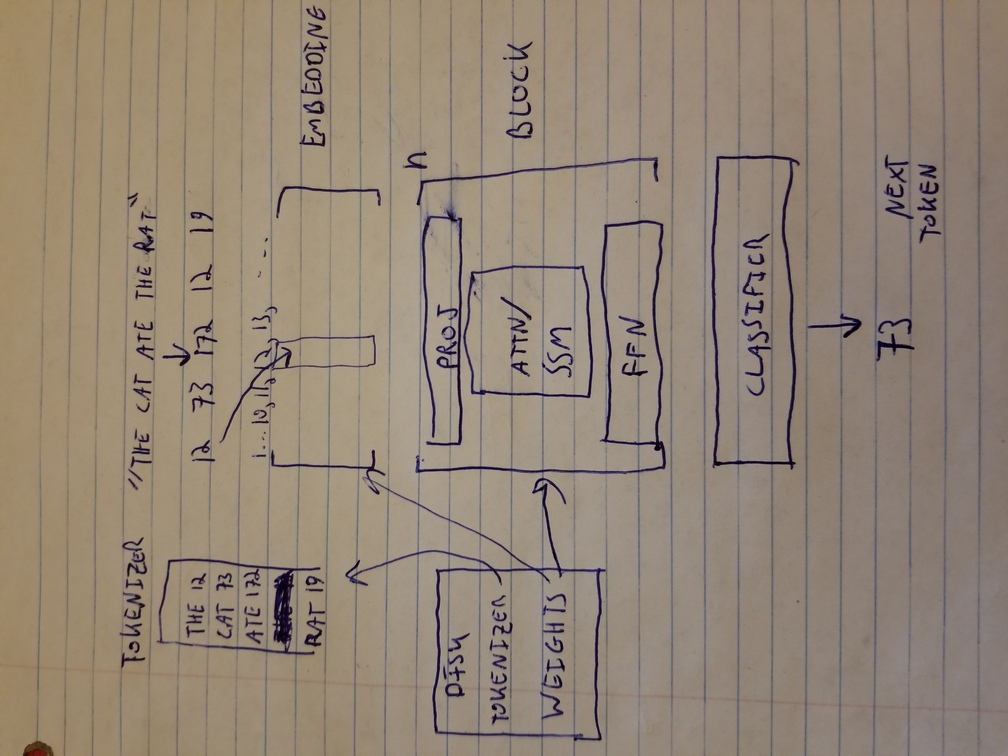

My goal is just to mention that a language model has a “tokenizer” that maps words or parts of words to numbers, and “weights” that take part in some linear algebra to calculate the next token based on previous ones and in this way generate sentences. The process is shown below. The tokenizer and weights start on the hard disk and these are what are distributed as an AI model. During operation, they are loaded into memory. A crude summary of what goes on is that each token gets transformed into an array called an embedding that ideally captures all the properties of that word. The embedding is then processed by a series of blocks that make up the model, that include some matrix multiplication, an attention (or other mechanism) block that performs the core function of relating the current token to previous ones, and some more neural network layers that are essentially matrix multiplication. After some number of layers are applied, the result goes through a classifier (another matrix multiplication) to determine the most probable next token.

Sketch of LLM architecture

TLDR, the language model has to do lots and lots of matrix multiplication (actually matrix-vector multiplication for inference) typically involving many Gigabytes of weights. The speed of the program depends almost entirely on how fast it can do a dot product, that is multiply two lists of numbers together element by element and add the results. And importantly, this hinges on how quickly the data can be retrieved from the computer’s memory and brought to the CPU.

The weights are stored in memory in a structure that looks something like this for llama:

type TransformerWeights

real(kind=wp), allocatable :: token_embedding_table(:,:)

real(kind=wp), allocatable :: rms_att_weight(:,:)

real(kind=wp), allocatable :: rms_ffn_weight(:,:)

real(kind=wp), allocatable :: wqkv(:,:,:)

real(kind=wp), allocatable :: wo(:,:,:)

real(kind=wp), allocatable :: w13(:,:,:)

real(kind=wp), allocatable :: w2(:,:,:)

real(kind=wp), allocatable :: rms_final_weight(:)

real(kind=wp), allocatable :: wcls(:,:)

end type TransformerWeights

The 3D (:,:,:) weights as well as the rms_attn and rms_ffn weights are for the repeated blocks.

The only material parts of implementing LLM inference then are loading in the data, implementing the tokenizer, and quickly multiplying matrices. The actual order and particulars of the multiplications is model dependent and I’m not going to describe it here.

File formats and loading

Almost all AI models are (unfortunately) distributed in Pytorch binary format which is not easily worked with outside of Pytorch. (There is also SafeTensors which I admit I know nothing about). Luckily Llama.cpp, a C++ language model framework has developed the a GGUF7 format that is easy to work with, and conversion utilities. The format includes key-value pairs with metadata and then offsets to the weights in their uncompressed format. Best of all, Llama.cpp includes a conversion utility8 that not only converts Pytorch models but also quantizes them. Quantization is important because most? (seemingly, I don’t have stats) models are distributed in 32-bit format but can be reduced to 16-bits without sacrificing quality or to fewer bits per weight with some quality hit. The size reduction is important because it lets a bigger model fit in memory but also because it can speed up models that are memory bandwidth limited as the data reaches the CPU faster. I haven’t checked this comprehensively but for example it’s faster to load 16-bit data, convert to 32-bits and multiply than it is to load and multiply 32-bits directly using AVX2 instructions on my machine.

The llama.cpp conversion utility supports many common models including llama2. In the case of Distilbert, it was not supported and I had to add it9. This essentially boils down to adding a description of the model architecture and mapping the names of the weights to the names used in GGUF as shown in the linked commit, and it much easier than doing it from scratch. At the time of writing I have not added support for Mamba yet. GGUF also includes the tokenizer data (vocabulary and scores) in the file format.

I wrote a pure Fortran script that loads both the weights and vocabulary from a GGUF file10.

Tokenizer

To keep the model dependency free I implemented simple byte-pair-encoding11 (BPE) and sentencepiece12 tokenizers that break input text into tokens and then numbers from the vocabulary. These I based on Andrej Karpathy’s implementation13 and a HF tutorial respectively. Although it keeps the code simple, it may be worth revisiting these because they are very simple implementations and may have problems on edge cases.

Fast math

Using 16-bit quantization, the core loop where the program spends time is on converting the weights from 16-bits to 32-bits and multiplying with a vector as it passes through the model, e.g.

do ix = 1,size(qkv)

qkv(ix) = dot_product(fp16_to_f32(xb),(w%wqkv(:,ix,l)))

end do

Here the matrix multiplication is written as a loop over dot products which empirically was faster and is easily parallelized (though in practice memory bandwidth makes this harder). On an Intel CPU with AVX2 and FP16 intrinsics, it is possible to write a vectorized function in C that implements the conversion and dot product as one i.e.14

float dot_product_fp16_fp32_v2(const float* input_fp32, const uint16_t* input_fp16, int size)

…

We can then call this from Fortran and link with -flto to provide link-time inlining in order to take advantage of the vectorized instructions. This could be modified as appropriate for different architectures.

Conclusion

These are some of the key points of why I used Fortran and what I had to do to implement an LLM, outside of actually typing the inference code which is pretty well understood. I’ve tried to keep this pretty light. The code is online for more detail or you can contact me with any questions. Note that I have pasted snippets from the Ferrite and llm.f90 projects, and form the master and optimize16/purefortran branches in the latter.

Future work includes more parallelism as I have been focusing on single-core optimization. More quantization options, and more debugging with other Fortran compilers, particularly Intel ifx. I may try and add other accelerator support (GPU etc.). Importantly, the goal is not to have a flexible program that can run many different models and support different hardware. It’s to provide a recipe for writing a custom implementation that meets one’s particular needs, in order to keep the complexity down.

https://github.com/rbitr/ferrite/blob/master/transformer.f90#L424↩︎

https://github.com/rbitr/llm.f90/blob/optimize16/purefortran/read_ggml.f90#L489↩︎

https://github.com/ggerganov/ggml/blob/master/docs/gguf.md↩︎

https://github.com/ggerganov/llama.cpp/blob/master/convert-hf-to-gguf.py↩︎

https://github.com/rbitr/llama.cpp/commit/93d7ab1ea819d950ce733714c1a64f7ba95e8dcf↩︎

https://github.com/rbitr/llm.f90/blob/optimize16/purefortran/read_ggml.f90↩︎

https://github.com/rbitr/llm.f90/blob/optimize16/purefortran/llama2.f90#L717↩︎

https://github.com/rbitr/ferrite/blob/master/transformer.f90#L393↩︎

https://github.com/karpathy/llama2.c/blob/master/run.c#L452↩︎

https://github.com/rbitr/llm.f90/blob/optimize16/purefortran/convert.c#L47↩︎