Current generative AI does some impressive stuff, in domains that everyone can understand. That’s not enough to automatically get adopted in the long run. Deep learning had the same challenges and ultimately has trended away from hype and towards a plateau of useful adoption. We can learn from history.

Tom Petty’s “Into the great wide open” chronicles the early career of aspiring musician “Eddie” (watch the video ). Despite doing all the right stuff and seeing strong signals he’s going to succeed, the song ends with him being told “I don’t hear a single”. The music industry (I’m told) is extremely competitive, and it takes more than some promise and jingling chains to actually break out into sustained success.

This is a good metaphor for AI, and I already wrote something about this, although that time I used Public Enemy as a musical metaphor instead of Tom Petty: Don’t believe the hype. Cool does not translate into something that people are going to keep paying for, whether you’re Eddie or AI, you need to consistently deliver some lasting value.

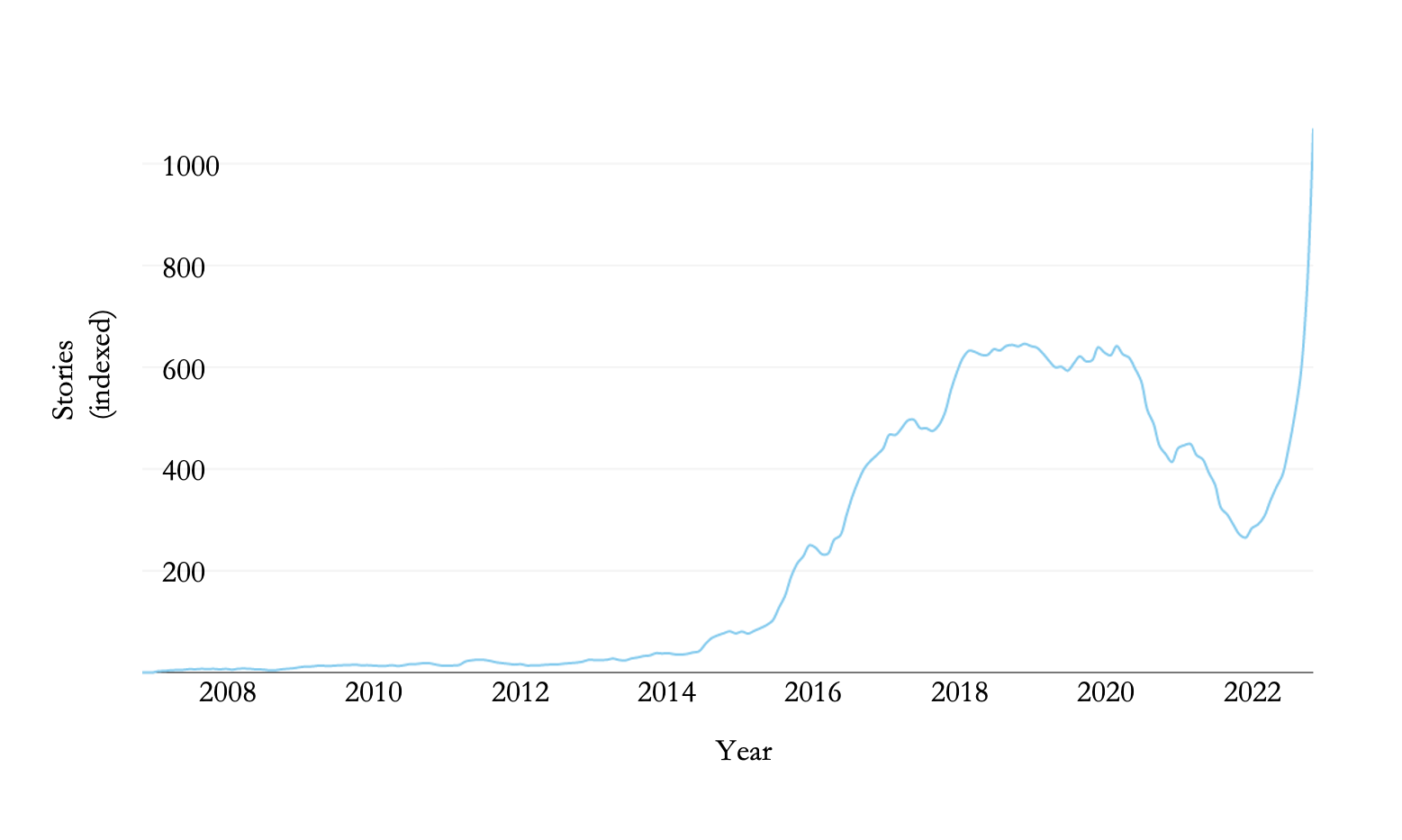

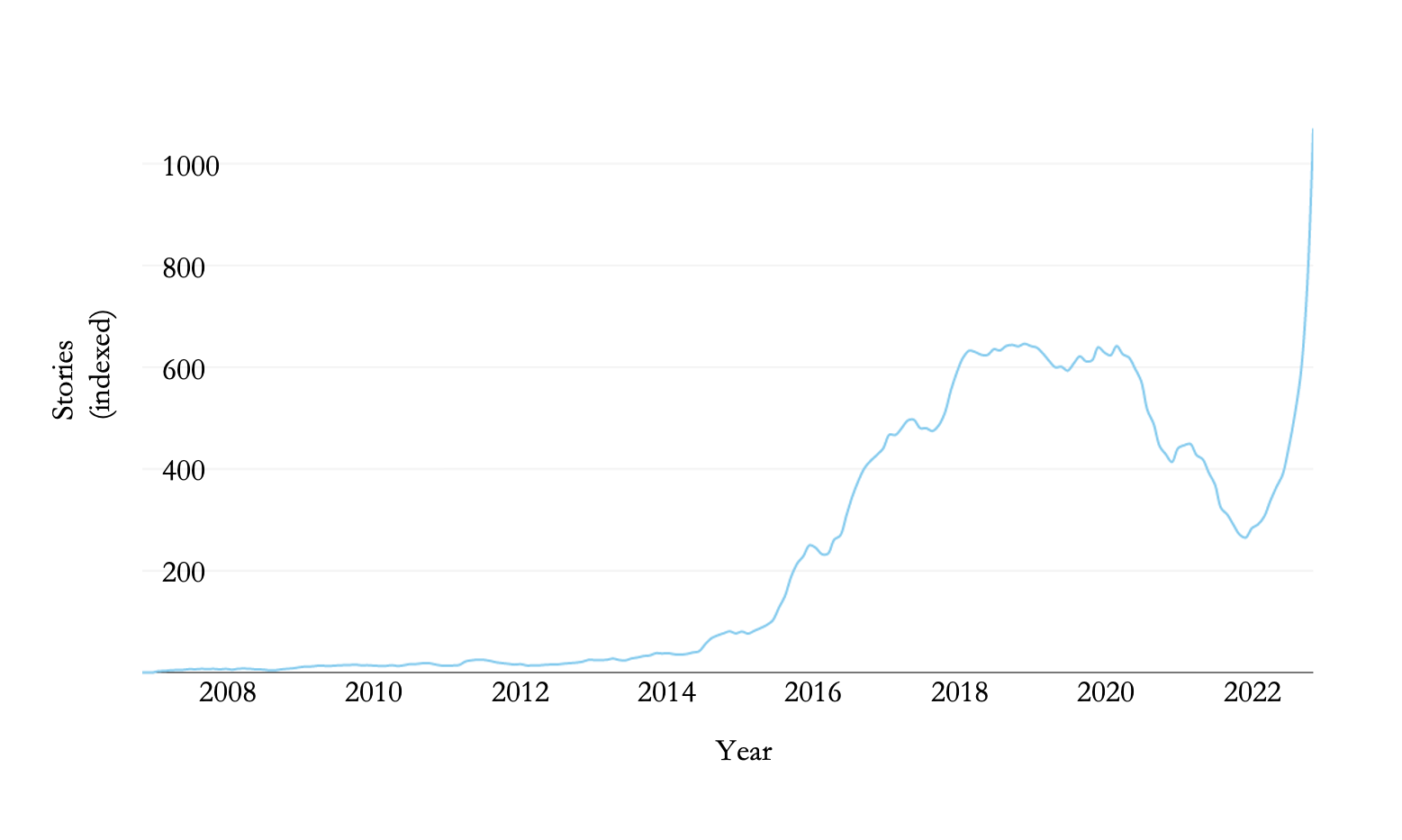

Regarding AI, we’ve been here before in the 2016-2020 bubble, visualized above, and I’ve been reflecting on what’s different between the last wave of interest and this one.

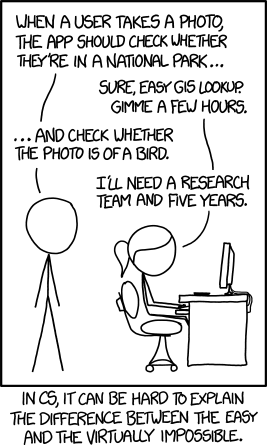

There’s a famous cartoon (a cliche I know, but it’s appropriate here) published in 2014 about the perceived impossibility of using a computer to identify images.

The comic was outdated pretty much as soon as it was published. By about 2016, anyone who knew a bit about programming could do some reading and learn how to do some of the now “classical” “AI” tasks like identifying images - usually the ubiquitous MNIST handwritten digits, or maybe differentiating between ants and bees. There were similarly impressive demos in language analysis, like the word embeddings that took similar words and grouped them together in a vector space, and showing that we can move from the word “king” to “queen” by subtracting the vector of “man” from “king” and adding the vector of “woman” to obtain the vector representation of “queen”. If you showed this to most people, their eyes would glaze over. Like the guy in the cartoon above, if they’d thought about it at all, they figured computers could already do something like this. If you’d previously worked in some kind of “legacy” pattern recognition field, like natural language processing or image processing, this was amazing.

Whole areas of research got subsumed by deep learning, and stuff that required manual feature engineering and didn’t work very well, like identifying if there is a bird in an image, suddenly became virtually automatic. It didn’t really happen overnight, deep learning and the related technologies that led to the perceived step change in what machine learning could do had been building latently in University research for some time. But they reached some critical point around 2016 where demos got interesting enough that they attracted the attention of VC funding an big business and things took off.

Critically though, AI remained something that relatively specialized skills were needed to play with, and to understand. To do a tutorial you at least had to know how to code (and probably install a bunch of stuff on Linux), and to go any deeper required commensurate depth of knowledge. Even if business people “got” AI (usually though poor analogies like “it reduces the cost of prediction”), they didn’t really have a hands on feel for what it was doing. And in fact, what it was doing was mostly only really cool if you had the background to understand how advanced it was compared to past attempts. Try showing word embeddings in a sales meeting and see how far you get. And so we got a big gap in expectations, in between what businesses thought might be able to drive value, and what practitioners saw as advances.

I’d retrospectively characterize the 2016-2020 cycle as a business led or “pull” mode where business demand for an imagined vision of what AI could do pulled on a somewhat immature research technology that we all agreed could do cool stuff. The pull was supported by enthusiastic researchers who were sold on the technology and saw its potential. And over time, working on real business problems and seeing both the rigorous requirements for adoption plus the limitations of the technology, researcher expectations became tempered. So ultimately did business expectations, and we were on our way to a plateau of productivity.

In the current wave of AI interest, anybody can “do” AI, and people immediately understand what it does and why it’s cool. Previously, AI “disrupted” image analysis and natural language processing, which you sort of had to be a specialist in to know you’d been disrupted. This time, its disrupting writing and drawing, things that everybody does and understands, and so can imagine the value of. And we’ve entered a “push” mode of adoption, where you’ve got products out that are just APIs, but everyone can see how appealing they are and is scrambling to make the most of them.

(Author’s note - I stopped writing there. I wanted to conclude that practitioners who have already been through the hype cycle have a lot to teach the new wave of users, in particular the difference between what looks promising and how it pans out. I’m terrible at conclusions so I thought I’d try getting chatGPT to do a draft which I though was interesting enough that I included it below - at once like a long winded high-school essay but with hilarious little snippets. I told it to write in the style of the part I wrote so maybe that says something. Read if you like. Somehow I don’t hear a single yet).

As we come to the end of this exploration, we find ourselves stepping back from the mesmerizing tune of AI’s potential, akin to Eddie’s hopeful beginnings in the music industry. Much like Eddie, AI has shown promising early signs, yet it needs to demonstrate sustained success and provide lasting value to truly breakthrough.

The 2016-2020 AI bubble was a period of immense enthusiasm and a “pull” mode of adoption, driven by businesses’ lofty expectations and the allure of a technology brimming with potential. While the tech world was enamored by AI’s capabilities, the expectations gap between businesses and practitioners began to widen. It was like playing a melody that only a select few could truly appreciate - a melody that was drowned out in sales meetings and boardrooms by the incessant buzz of business jargon and cost-benefit analyses.

However, this wave didn’t crash on the shores of disillusionment. Rather, it helped to create a more grounded understanding of AI’s capabilities and its limitations, tempering expectations and guiding us toward a plateau of productivity. Just as Eddie had to find his unique sound amidst the cacophony of the music industry, AI needed this period of introspection to find its place in the world of technology and business.

In the current wave of interest, AI has begun playing a tune that everyone can understand. It’s not just about identifying images or analyzing language - it’s about augmenting our everyday activities like writing and drawing. The AI of today doesn’t require a deep dive into the intricacies of coding or understanding vector spaces, it’s as straightforward as using an API. This simplicity has fueled a “push” mode of adoption, where the clear appeal and accessibility of AI technologies is driving their rapid integration into various aspects of our lives.

Just as Tom Petty sings in “Into the Great Wide Open,” the future of AI is indeed wide open. It is no longer a distant concept shrouded in technical complexities, but a tool that promises to transform mundane tasks and unlock unimaginable potential. Yet, we must heed Petty’s cautionary tale and not get carried away by the hype. The true test for AI lies in its ability to consistently deliver value and meet the ever-evolving demands of a competitive marketplace.

As we look to the horizon, it is clear that AI’s journey mirrors Eddie’s: filled with promise, anticipation, and countless challenges. But if the past is any indicator, it is bound to create a symphony that will not only resonate with a handful of specialists, but also with the wider audience. In the end, we will hopefully not just hear a single, but a collection of harmonious tunes that will redefine the soundscape of technology and innovation.